TEEN CONCEPTUALISM / DIDACTIC CONCEPTUALISM

By Francisco Lemus, curator of the exhibition.

What role did conceptualism play in the Buenos Aires art scene of the nineteen-nineties? Conceptualism is often left aside when we talk about that decade, which is associated with global neo-conceptualism, a practice seen as antithetical to the curatorial vision of the Centro Cultural Rojas gallery. Conceptualism’s relationship with humor and play, with the alternative scene’s visual culture and strategies, is rarely examined. It is, rather, seen as a cold experience rife with signs that must be interpreted, a movement closely tied to the politicization of art. This exhibition contains a group of works that provides an alternative answer to the question about conceptualism formulated above. That said, not all of these works were conceived as conceptual; they are elusive in terms of both aesthetic and discipline—and therein lies their charm. But I put out this idea in order to approach the nineties from an angle largely overlooked, to explore a critical vision suggested in the first chapter. While I propose looking at these works through the prism of conceptualism, I would like to point out the impurity of their images and how hard they are to catalogue (that is exactly why they are so jarring for official art histories).

Read more...

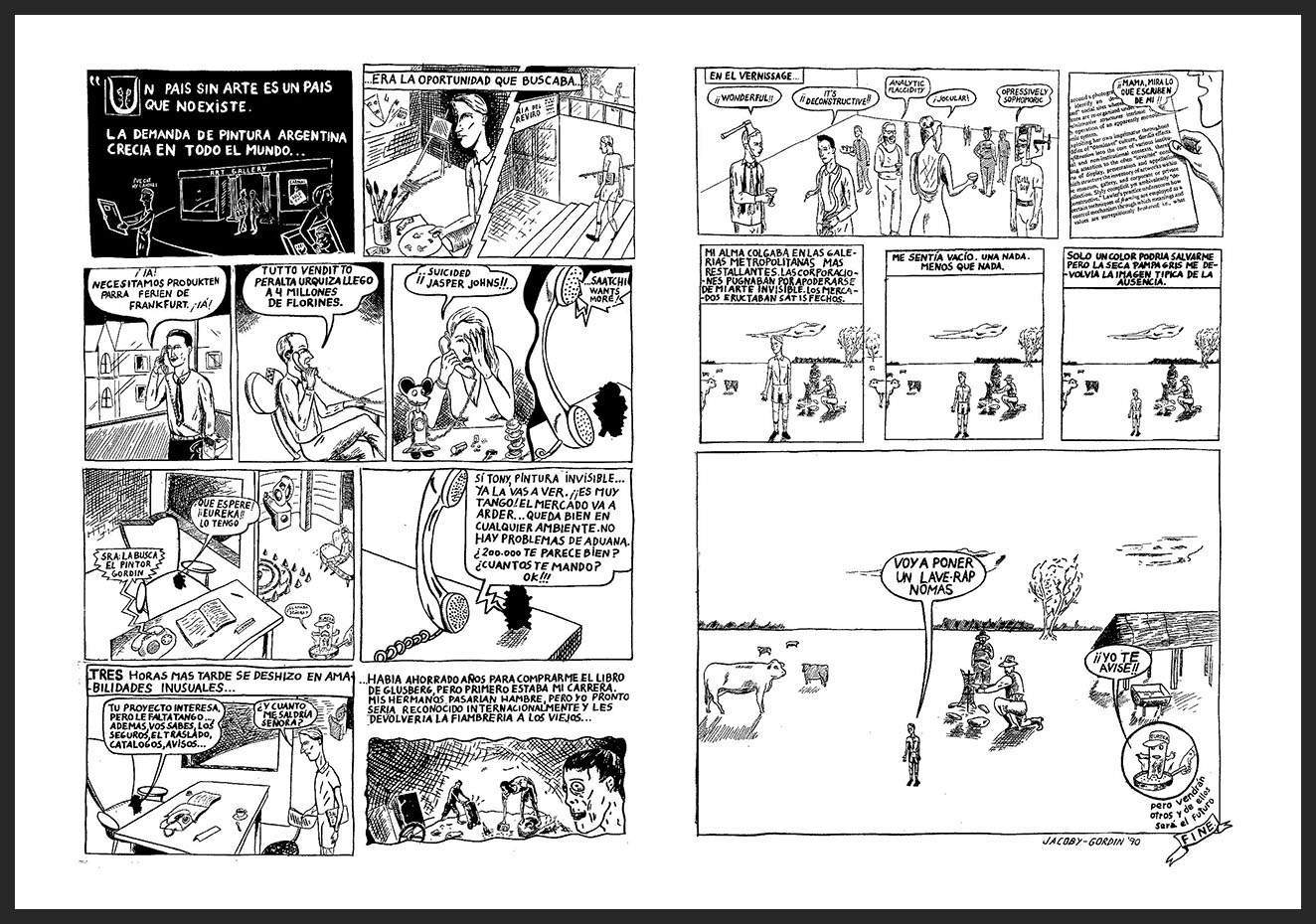

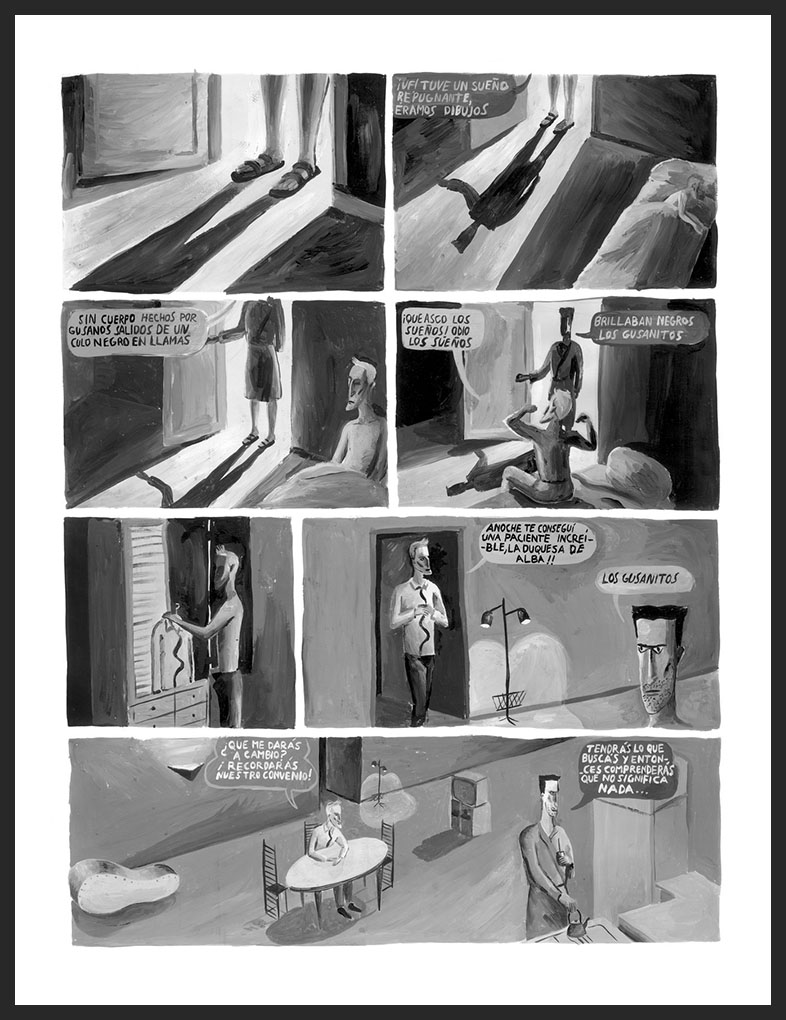

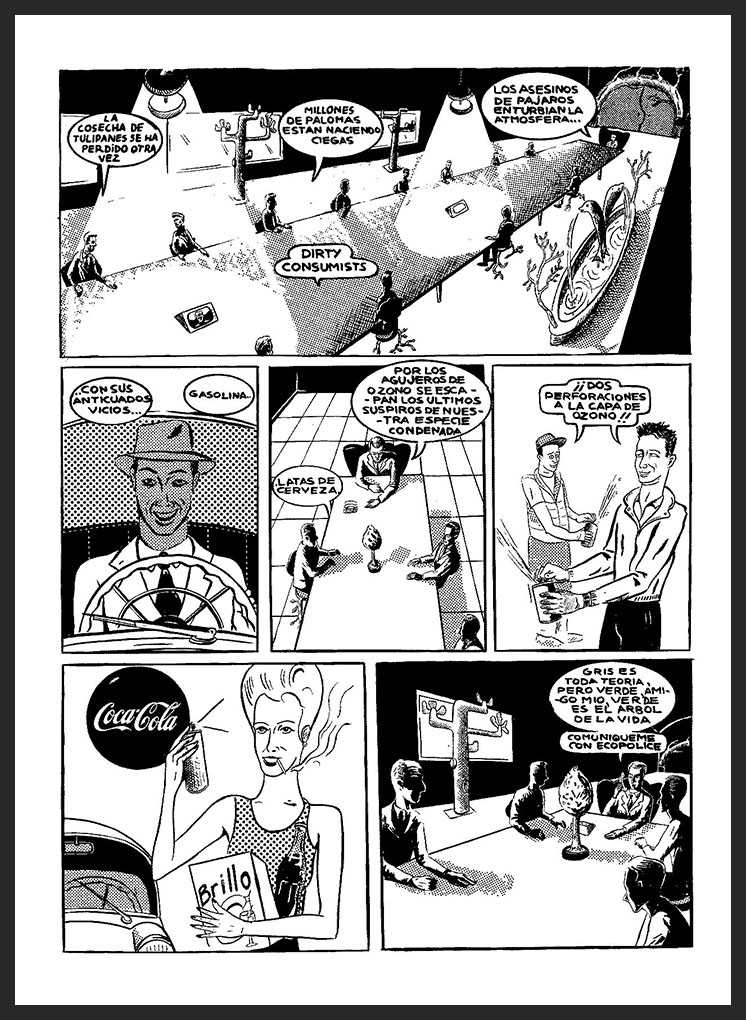

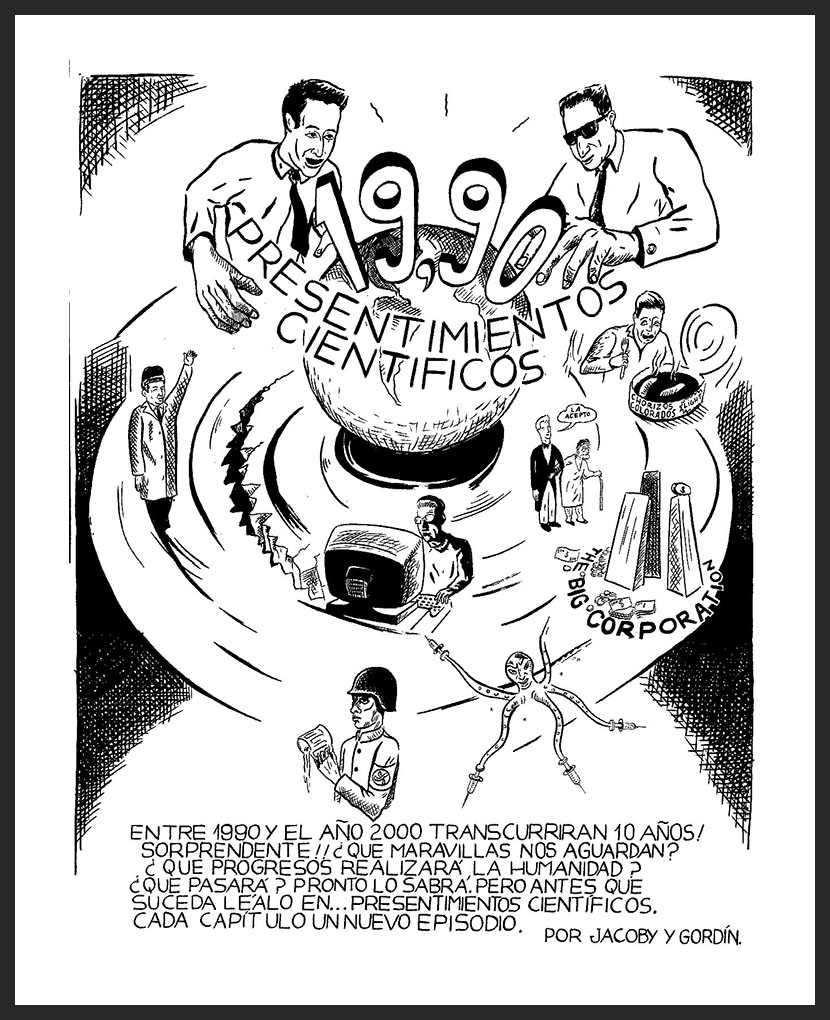

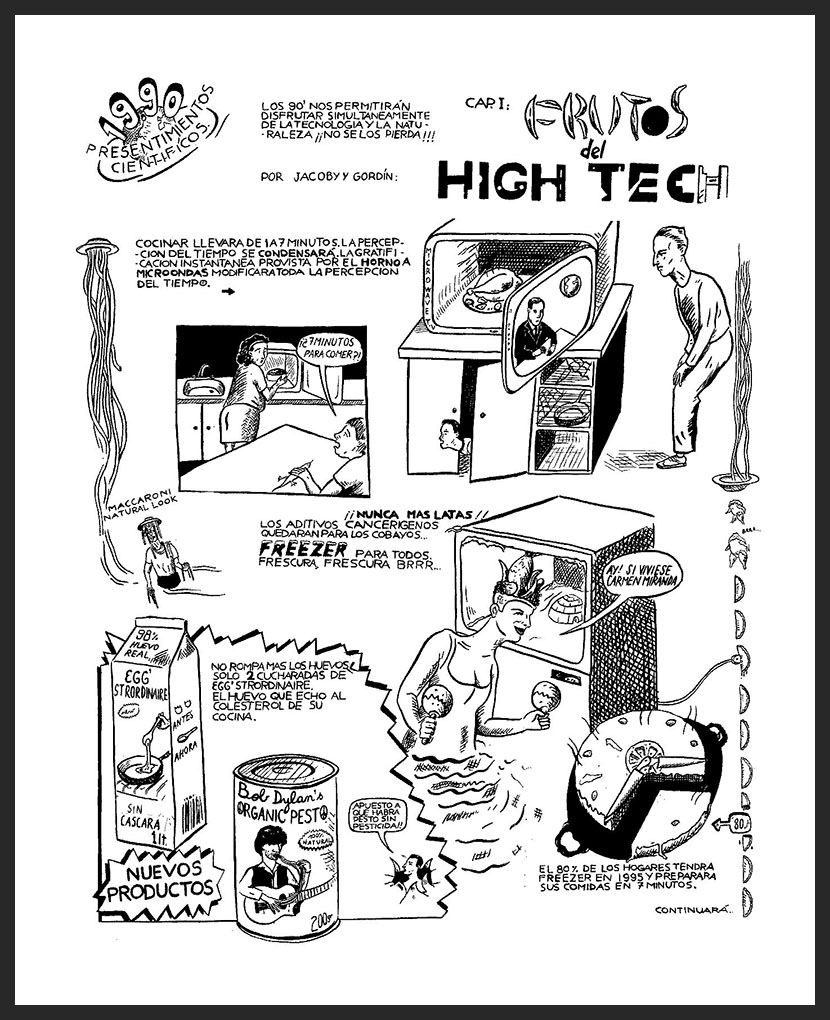

The first works share a marginal position in the art world. They engage the local art scene ironically as, in the nineties, new artists and venues were changing its configuration. Comics by Roberto Jacoby and Sebastián Gordín produced in 1989 and 1990 were created for publication in the magazine Fierro. The vision of art history, museums, and the longed-for “internationalization” of Argentine art suggested in these works is tinged with sarcasm. The comics mix local celebrities with facets of Argentine culture and life such as psychoanalysis and endless economic crises. They show apocalyptic scenes tied to the end of history and the technological advances part and parcel of the late twentieth century.

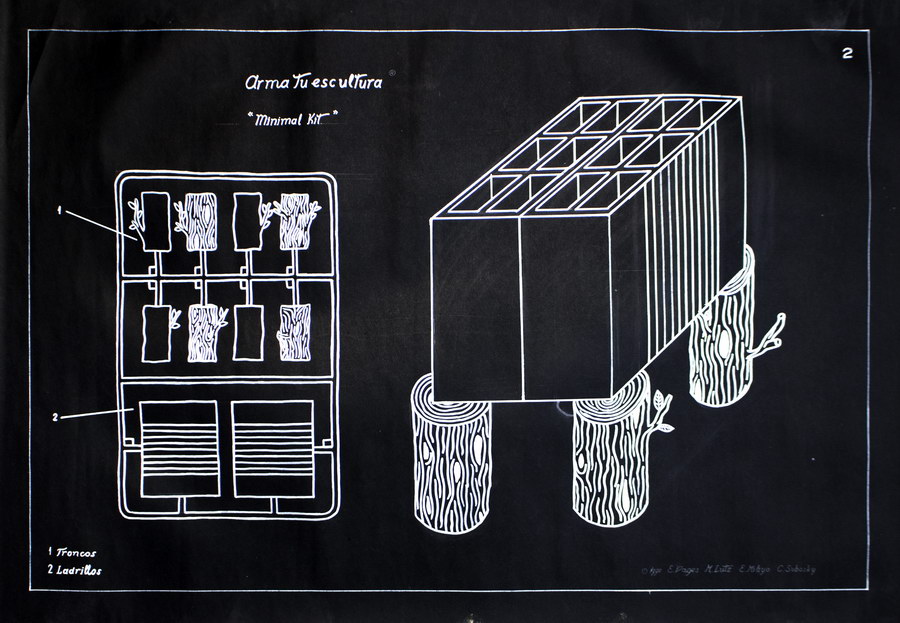

In winter of 1990, Carlos Subosky, Esteban Pages, Emiliano Miliyo, and Máximo Lutz undertook what would be their final joint project, Esculturas y Fotografías (Sculptures and Photographs). Months before, the group Mariscos en tu Calypso, which included Gordín and Fernando “Coco” Bedoya as well, had disbanded. That group, formed at the Manuel Belgrano Art Academy, was bound by a shared interest in, among other things, comics, the Italian trans-avant-garde, Pop art, music, and film. In the late eighties, the Mariscos were somewhat anti-system in their logic and workings; they frequented and exhibited in countercultural venues like the discotheque Cemento, Medio Mundo Varieté theater, and the José Ingenieros library. Their vision of the mainstream art circuit was acerbic. For Esculturas y Fotografías, the artists left a model airplane kit on the doorsteps of curators, critics, gallerists, and artists, and then secretly photographed them. The photographs drew a sort of map of the arts against the backdrop of a city of stark contrasts. Seen in one of the photographs is the entrance to the Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana (ICI), a key artistic and cultural space for young artists directed by Laura Buccellato at the time. It was at the ICI that Sebastián Gordín gave guided tours of a small model of an imaginary show housed in that very venue.

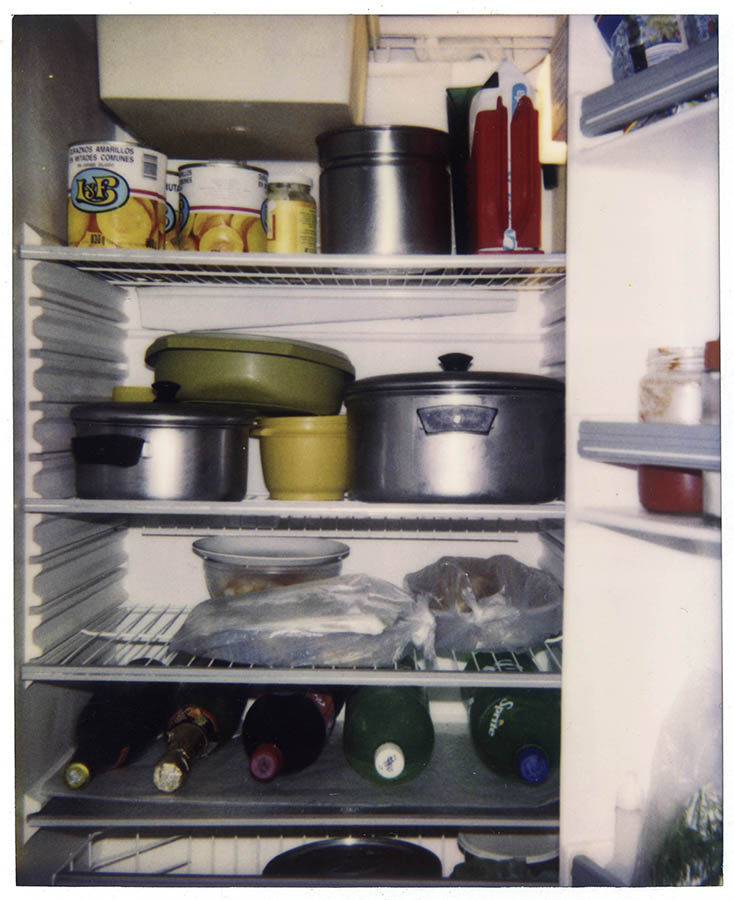

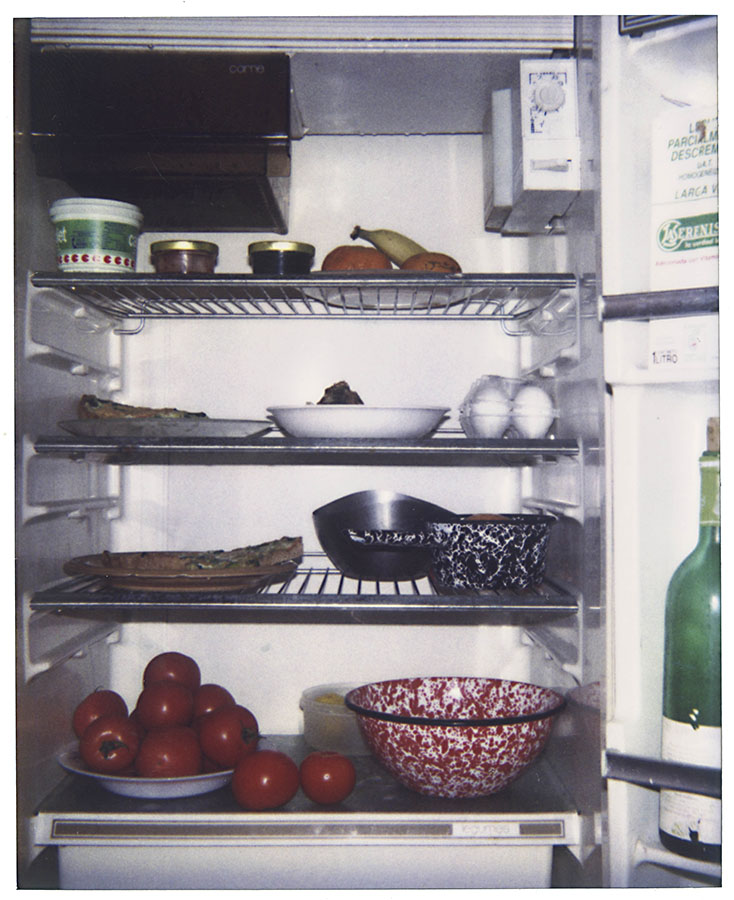

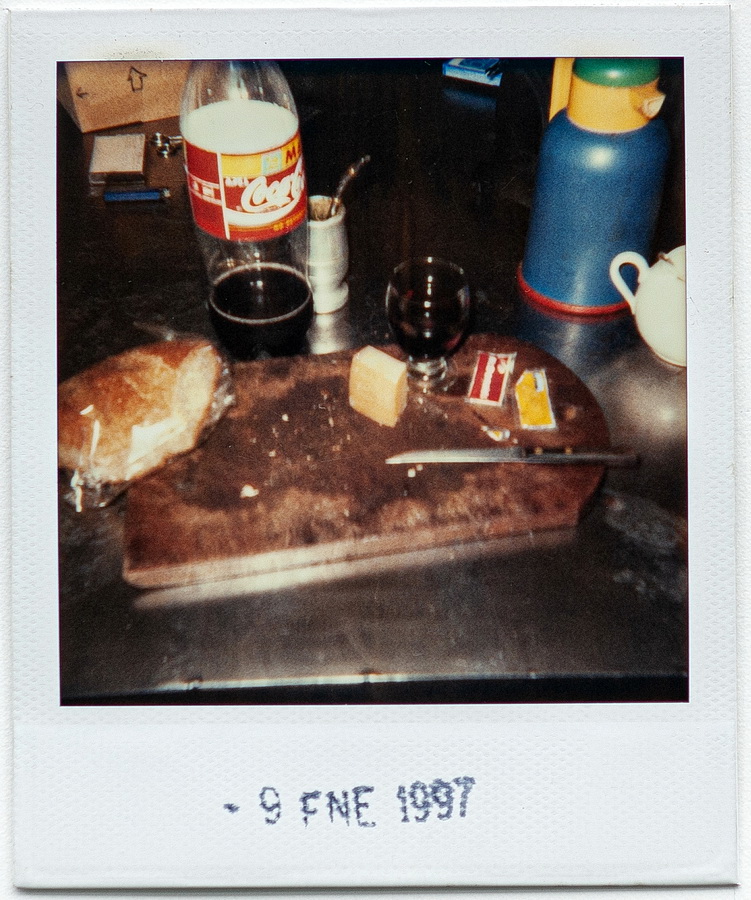

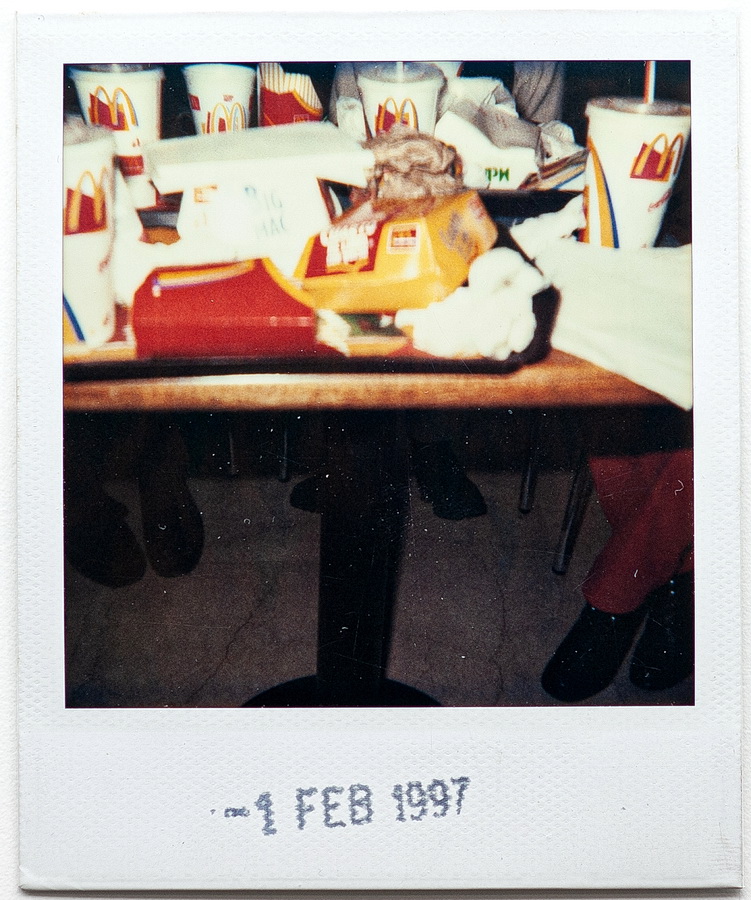

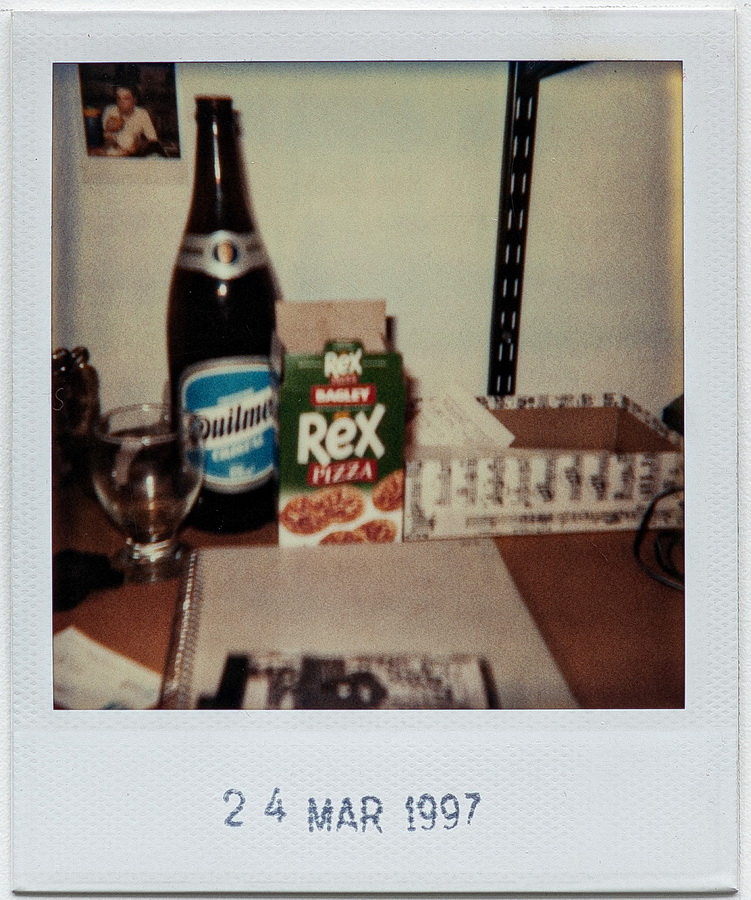

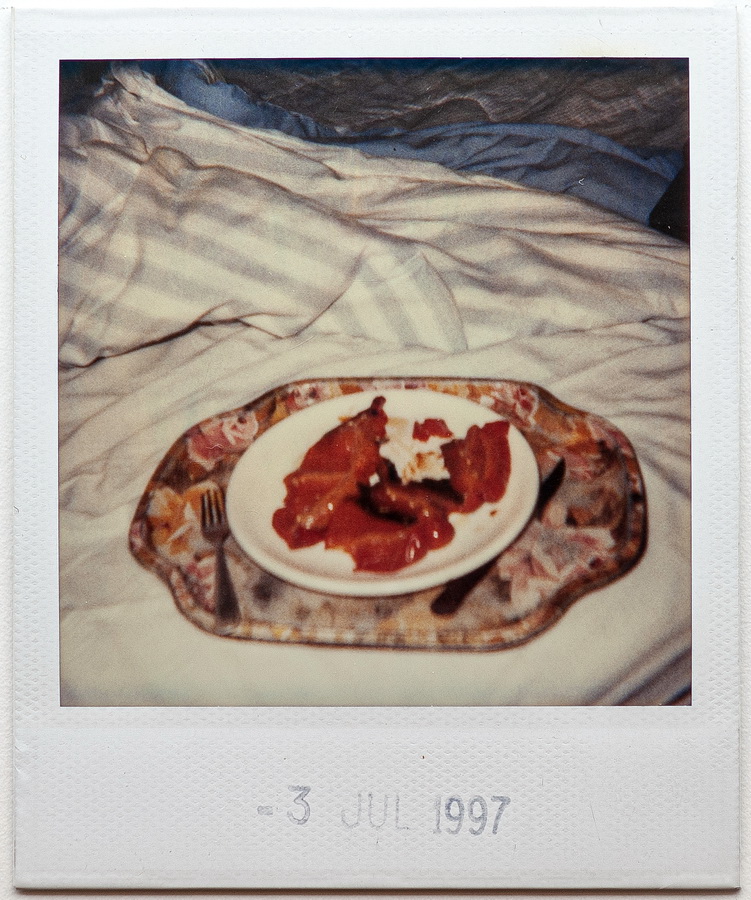

Photography underwent changes in the nineties: “contaminated” by contemporary art, it began to break away from its testimonial function. The opening of the Centro Cultural Rojas photo gallery in 1995 under Alberto Goldenstein was a turning point in ways of envisioning photography. The limits of the discipline were questioned at interdisciplinary critiques and studio classes. Raúl Flores’s photographs were part of that transformation. They show kitchen sinks brimming with dirty dishes and refrigerators full of alcohol and commonplace, cheap food in what were arguably still lifes of the nineties. For Flores, photography is what is there, what is in the most immediate environment. There is no need to stylize an image; experimentation and sentimentality must be curbed in photographic practice to avoid grandiloquence.

In 1994, Rosana Fuertes showed Los 60 no son los 90 (The Sixties are not the Nineties) at Fundación Banco Patricios. The work consisted of five rows of small painted cardboard t-shirts bearing different images. Che Guevara’s iconic face on a red shirt; a flower with the title of the work and the face of Carlos Menem, president at the time, on a pink shirt (that color was associated with Argentine art of the nineties). Fuertes, who had studied with Pop artist Pablo Menicucci in Mar del Plata, was also a grade-school teacher. In her works from those years, she made use of symbols from Argentine history as well as the country’s customs and visual culture. Pop images were treated conceptually to yield the tidiness associated with school supplies and graphic design. At first, her works seem didactic, a sort of sampler of the alienated consumerism characteristic of the nineties in Argentina. Notwithstanding, just beneath the surface in each t-shirt are the tensions that afflicted an art field grappling with art’s social and political role.

ORGULLO Y PREJUICIO

Art in Argentina in the 90 and beyond.Chapter I. Introduction.

Chapter II. Teen Conceptualism / Didactic Conceptualism