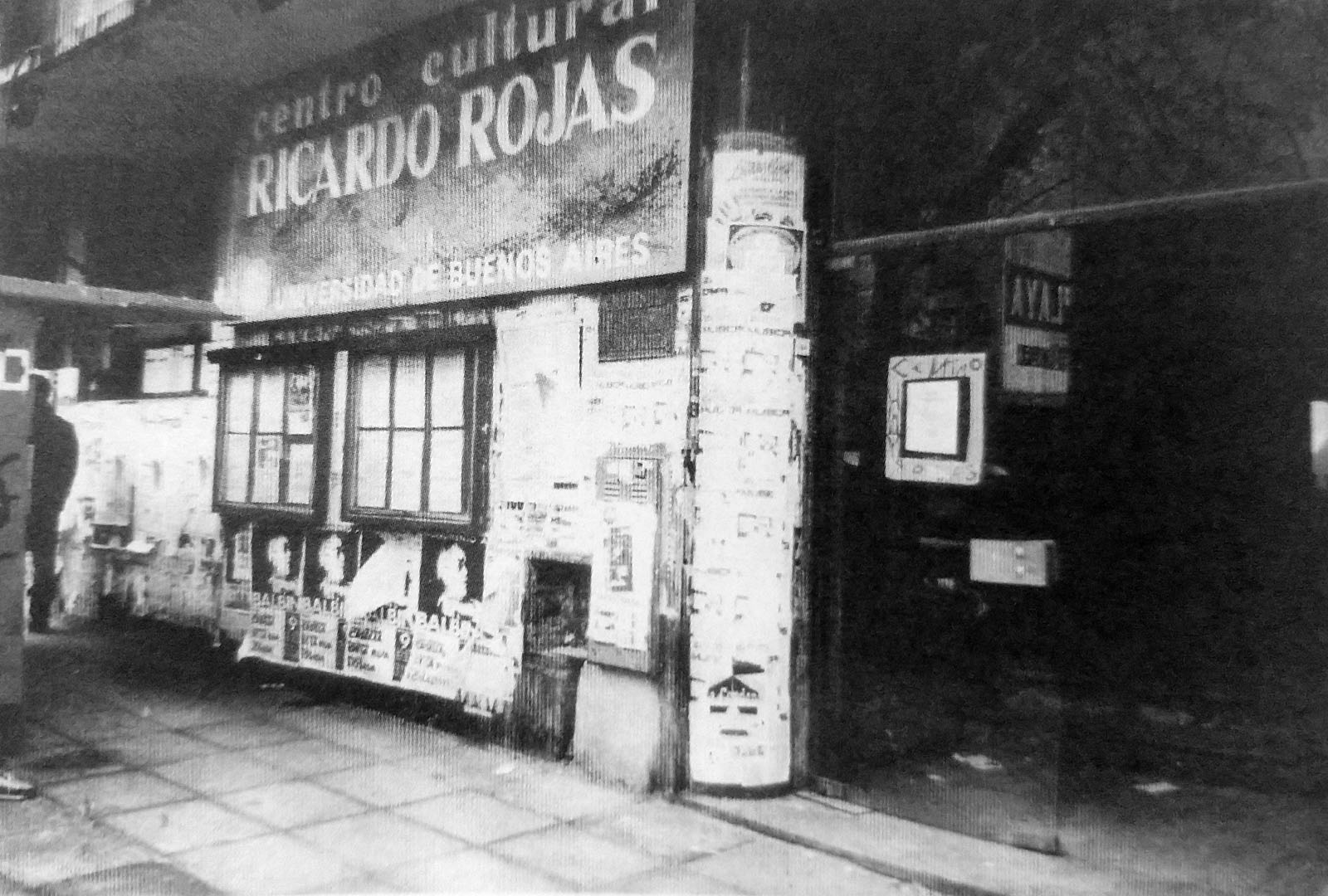

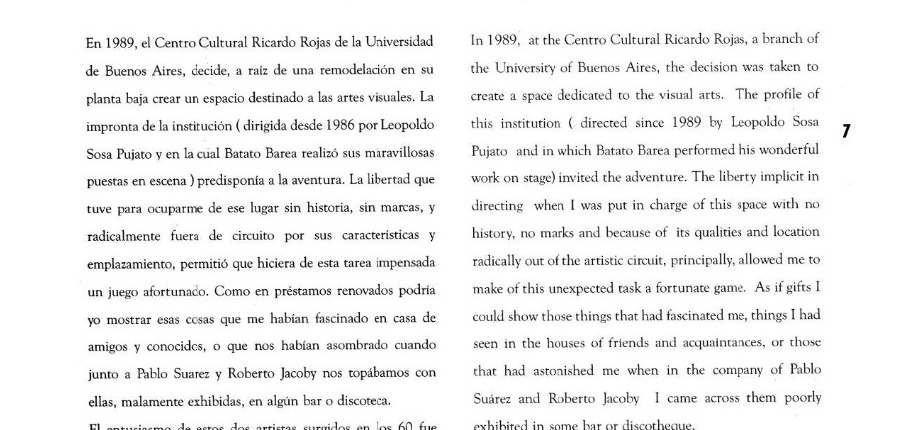

The online exhibition Orgullo y Prejuicio (Art in Argentina in the 90s and Beyond) reaffirms one of the gallery’s primary points of interest: to investigate and communicate experiences and artists emblematic of contemporary art from Argentina. The pandemic has turned our gaze inward and reinforced emphasis on the local. The notions of “situated” institutions and collections and of “cosmopolitan provincialism” are key to our thinking, and that implies underscoring, understanding, translating, and communicating the impulses and modalities at play in artistic practices that take shape here, in Argentina’s urban space. It implies as well savoring the histories, stories, and subjectivities, in all their nuances, complexities, and subtleties, that inevitably partake of the dialectic between global movements and the conditions particular to this part of the world.

We have invited art historian and curator Francisco Lemus, a specialist in Argentine art from the nineteen-nineties, to develop an online exhibition that, while based on the artists represented by the gallery, expands to include other fundamental figures. The conviction behind this project is that the nineties witnessed developments crucial to Argentine art, that the vectors and lines of force that that decade generated remained active for the decades that followed, and even shed light on recent art. The exhibition is envisioned as a tree trunk—this first section is its base—off of which interconnected branches sprout in the installments to be uploaded during the months remaining in 2020. The next installment will be Teen Conceptualism and Didactic Conceptualism.

“Art acted like an air shaft, a small crack to let in sensibility in a gravely hostile context. From the alternative to the mainstream, art was influenced by fashion, music, and youth culture. And as that influence grew, the virus spread. Creativity was experienced intensely as friends and lovers were bid farewell. Beauty and death comingled.”

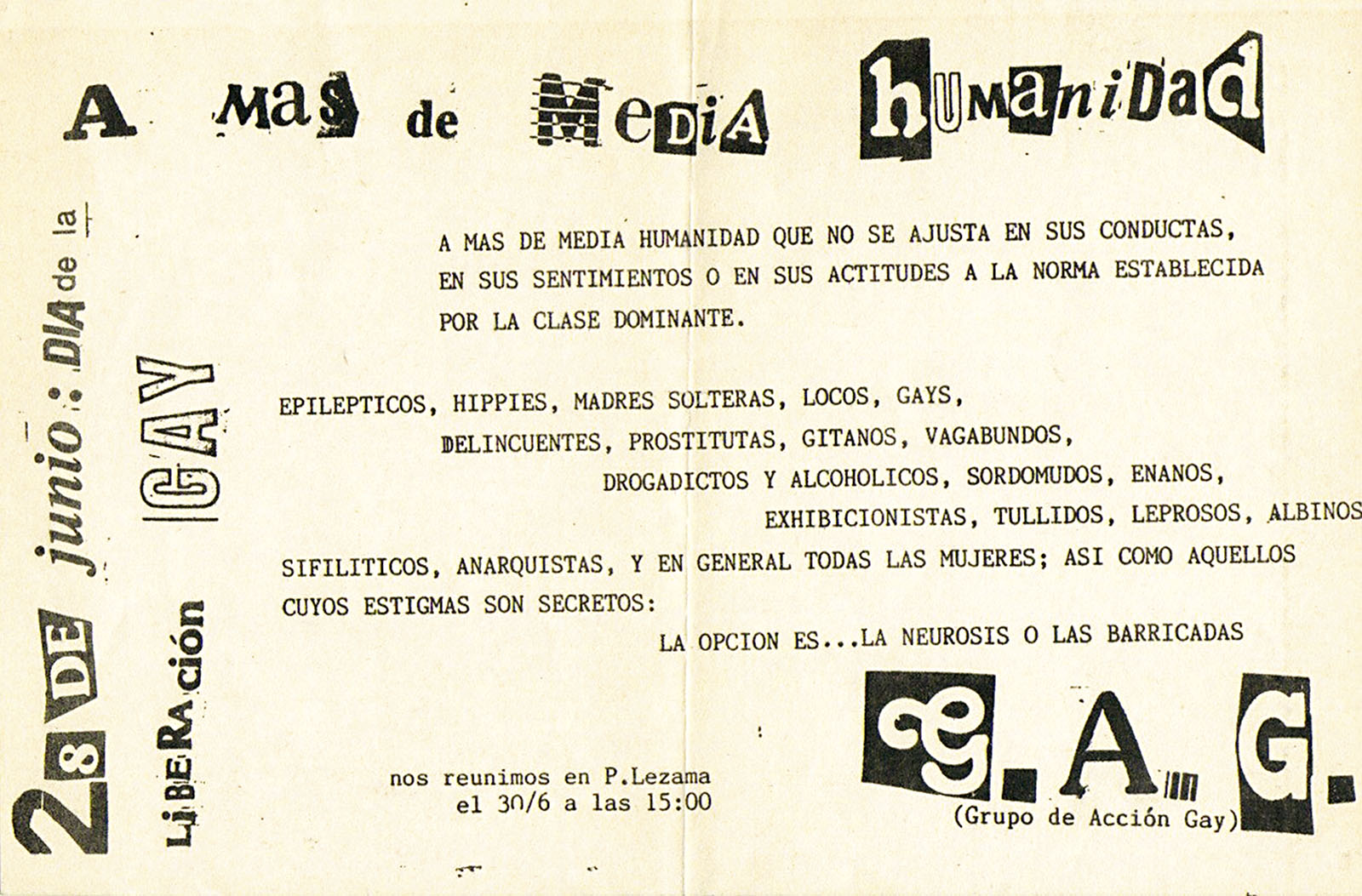

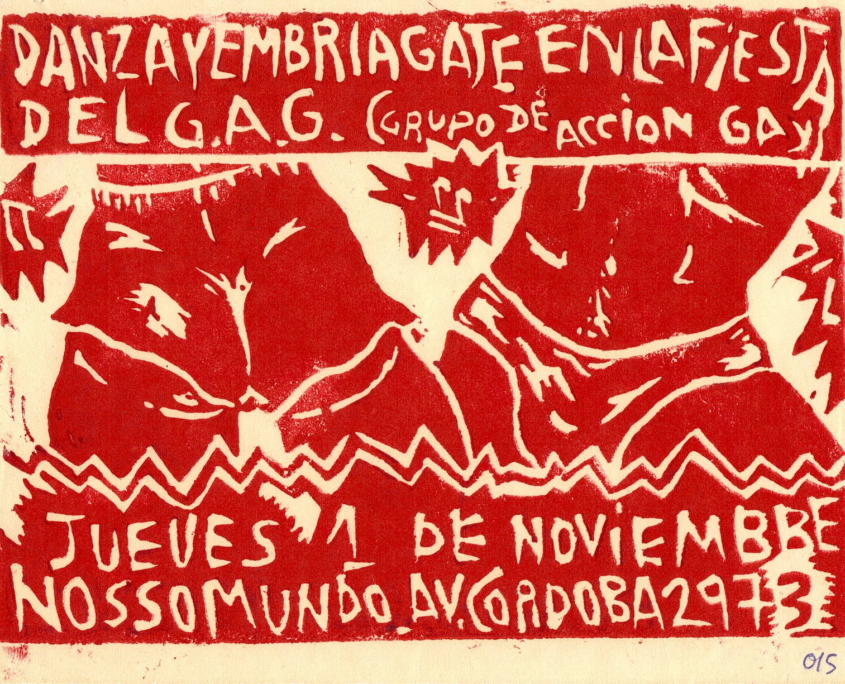

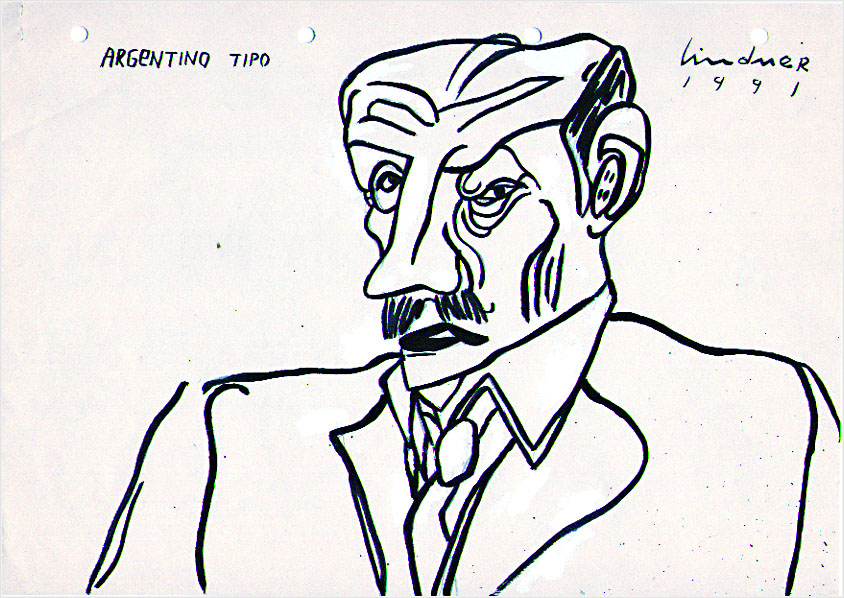

For artists’ bios and additional information on artworks and documents, please click on each image